11장 Modules, Packages, and Goodies

Table of contents

- Modules and the import Statement

- Packages

- Goodies in the Python Standard Library

- More Batteries: Get Other Python Code

- Coming Up

- Things to Do

During your bottom-up climb, you’ve progressed from built-in data types to constructing ever-larger data and code structures. In this chapter, you finally learn how to write realistic whole programs in Python. You’ll write your own modules and learn how to use others from Python’s standard library and other sources.

The text of this book is organized in a hierarchy: words, sentences, paragraphs, and chapters. Otherwise, it would be unreadable pretty quickly.^1 Code has a roughly similar bottom-up organization: data types are like words; expressions and statements are like sentences; functions are like paragraphs; and modules are like chapters. To continue the analogy, in this book, when I say that something will be explained in Chapter 8, in programming that’s like referring to code in another module.

Modules and the import Statement

We’ll create and use Python code in more than one file. A module is just a file of any Python code. You don’t need to do anything special—any Python code can be used as a module by others.

We refer to code of other modules by using the Python import statement. This makes the code and variables in the imported module available to your program.

Import a Module

The simplest use of the import statement is import _module_ , where _module_ is the name of another Python file, without the .py extension.

Let’s say you and a few others want something fast for lunch, but don’t want a long discussion, and you always end up picking what the loudest person wants anyhow.

Let the computer decide! Let’s write a module with a single function that returns a random fast-food choice, and a main program that calls it and prints the choice.

The module (fast.py) is shown in Example 11-1.

Example 11-1. fast.py

from random import choice

places = ['McDonalds", "KFC", "Burger King", "Taco Bell",

"Wendys", "Arbys", "Pizza Hut"]

def pick(): _# see the docstring below?

"""Return random fast food place"""_

return choice(places)

And Example 11-2 shows the main program that imports it (call it lunch.py).

Example 11-2. lunch.py

import fast

place = fast.pick()

print("Let's go to", place)

If you have these two files in the same directory and instruct Python to run lunch.py as the main program, it will access the fast module and run its pick() function. We wrote this version of pick() to return a random result from a list of strings, so that’s what the main program will get back and print:

$ python lunch.py

Let's go to Burger King

$ python lunch.py

Let's go to Pizza Hut

$ python lunch.py

Let's go to Arbys

We used imports in two different places:

- The main program lunch.py imported our new module fast.

- The module file fast.py imported the choice function from Python’s standard library module named random.

We also used imports in two different ways in our main program and our module:

- In the first case, we imported the entire fast module but needed to use fast as a prefix to pick(). After this import statement, everything in fast.py is available to the main program, as long as we tack fast. before its name. By qualifying the contents of a module with the module’s name, we avoid any nasty naming conflicts. There could be a pick() function in some other module, and we would not call it by mistake.

- In the second case, we’re within a module and know that nothing else named choice is here, so we imported the choice() function from the random module directly.

We could have written fast.py, as shown in Example 11-3, importing random within the pick() function instead of at the top of the file.

Example 11-3. fast2.py

places = ['McDonalds", "KFC", "Burger King", "Taco Bell",

"Wendys", "Arbys", "Pizza Hut"]

def pick():

import random

return random.choice(places)

Like many aspects of programming, use the style that seems the most clear to you.

The module-qualified name (random.choice) is safer but requires a little more typing.

Consider importing from outside the function if the imported code might be used in more than one place, and from inside if you know its use will be limited. Some people prefer to put all their imports at the top of the file, just to make all the dependencies of their code explicit. Either way works.

Import a Module with Another Name

In our main lunch.py program, we called import fast. But what if you:

- Have another module named fast somewhere?

- Want to use a name that is more mnemonic?

- Caught your fingers in a door and want to minimize typing?

In these cases, you can import using an alias, as shown in Example 11-4. Let’s use the alias f.

Example 11-4. fast3.py

import fast as f

place = f.pick()

print ("Let's go to", place)

Import Only What You Want from a Module

You can import a whole module or just parts of it. You just saw the latter: we only wanted the choice() function from the random module.

Like the module itself, you can use an alias for each thing that you import.

Let’s redo lunch.py a few more times. First, import pick() from the fast module with its original name (Example 11-5).

Example 11-5. fast4.py

from fast import pick

place = pick()

print ("Let's go to", place)

Now import it as who_cares(Example 11-6).

Example 11-6. fast5.py

from fast import pick as who_cares

place = who_cares()

print ("Let's go to", place)

Packages

We went from single lines of code, to multiline functions, to standalone programs, to multiple modules in the same directory. If you don’t have many modules, the same directory works fine.

To allow Python applications to scale even more, you can organize modules into file and module hierarchies called packages. A package is just a subdirectory that contains .py files. And you can go more than one level deep, with directories inside those.

We just wrote a module that chooses a fast-food place. Let’s add a similar module to dispense life advice. We’ll make one new main program called questions.py in our current directory. Now make a subdirectory named choice and put two modules in it —fast.py and advice.py. Each module has a function that returns a string.

The main program (questions.py) has an extra import and line (Example 11-7).

Example 11-7. questions.py

from choice import fast, advice

print ("Let's go to", fast.pick())

print ("Should we take out?", advice.give())

That from choice makes Python look for a directory named choice, starting under your current directory. Inside choice it looks for the files fast.py and advice.py.

The first module (choice/fast.py) is the same code as before, just moved into the choice directory (Example 11-8).

Example 11-8. choice/fast.py

from random import choice

places = ["McDonalds", "KFC", "Burger King", "Taco Bell",

"Wendys", "Arbys", "Pizza Hut"]

defpick():

"""Return random fast food place"""

return choice(places)

The second module (choice/advice.py) is new, but it works a lot like its fast-food relative (Example 11-9).

Example 11-9. choice/advice.py

from random import choice

answers = ["Yes!", "No!", "Reply hazy", "Sorry, what?"]

def give():

"""Return random advice"""

return choice(answers)

If your version of Python is earlier than 3.3, you’ll need

__init__.pyin the sources subdirectory to make it a Python package. This can be an empty file, but pre-3.3 Python needs it to treat the directory containing it as a package.

Run the main questions.py program (from your current directory, not in sources) to see what happens:

$ python questions.py

Let's go to KFC

Should we take out? Yes!

$ python questions.py

Let's go to Wendys

Should we take out? Reply hazy

$ python questions.py

Let's go to McDonalds

Should we take out? Reply hazy

The Module Search Path

- 모듈 탐색 순서

- 현재디렉터리

- sys.path에서 확인된 순서

>>> for i in sys.path:

... print(i)

...

C:\Users\neo21\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python311\python311.zip

C:\Users\neo21\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python311\Lib

C:\Users\neo21\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python311\DLLs

C:\Users\neo21\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python311

C:\Users\neo21\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python311\Lib\site-packages

- 모둘 탐색 경로 추가

>>> import sys

>>> sys.path.insert(0, "/my/modules")

- 개인 모듈 일반 저장 위치

- Python311\Lib\site-packages

Relative and Absolute Imports

- 절대경로

import rougarou 탐색경로의 각 디렉터리에 대해 파이션은 rougarou.py(모듈), rougarou디렉터리(패키지)를 찾는다.

- 상대경로

rougarou모듈 import하기- 메인 프로그램과 동일 디렉터리에 있는 경우 :

from . import rougarou - 상위 디렉터리에 있는 경우 :

from .. import rougarou - 상위 디렉터리의 creatures 디렉터리에 있는 경우 :

from ..creatures import rougarou

- 메인 프로그램과 동일 디렉터리에 있는 경우 :

For a good discussion of Python import problems that you may run into, see Traps for the Unwary in Python’s Import System.

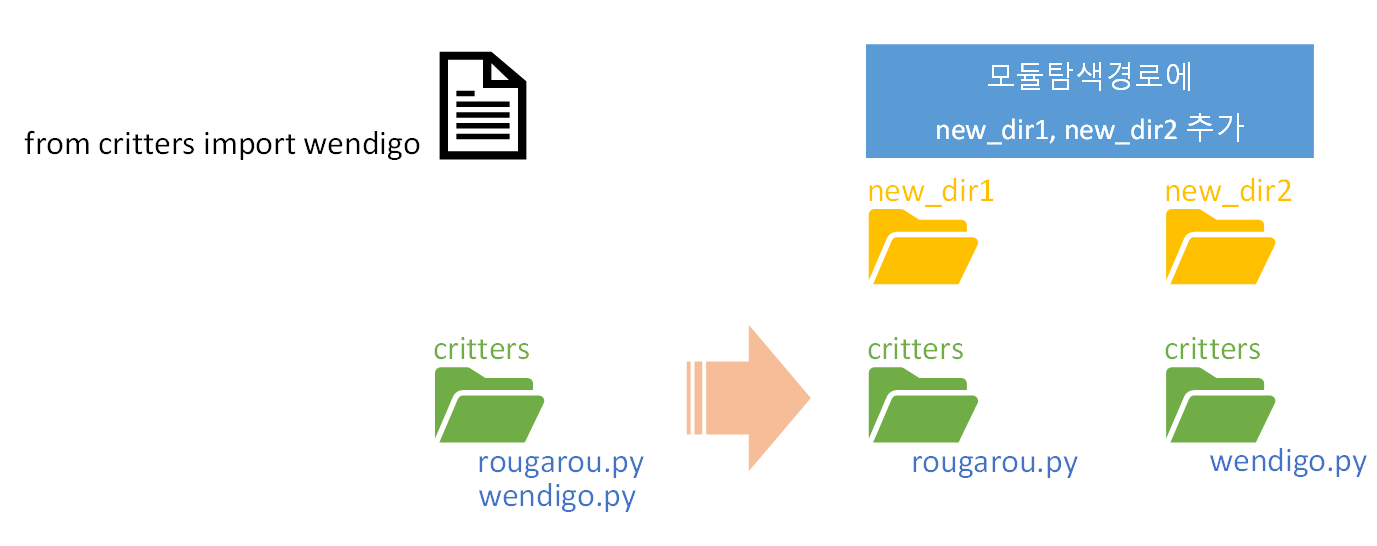

Namespace Packages

디렉터리 재분할 방법

- Make

new locationdirectoriesabove critters - Make

cousin crittersdirectoriesunder these new parents - Move

existing modulesto theirrespective directories.

- Make

This needs some illustration. Say we started with this file layout:

Modules Versus Objects

모듈을 두번이상 import하더라도 하나의 모듈 사본만 존재한다. 그러하므로 전역 변수 유지 가능

Goodies in the Python Standard Library

One of Python’s prominent claims is that it has “batteries included”—a large standard library of modules that perform many useful tasks. They are kept separate to avoid bloating the core language. When you’re about to write some Python code, it’s often worthwhile to first check whether there’s a standard module that already does what you want. It’s surprising how often you encounter little gems in the standard library.

Python also provides authoritative documentation for the modules, along with a tutorial. Doug Hellmann’s website Python Module of the Week and book The Python Standard Library by Example (Addison-Wesley Professional) are also very useful guides.

Upcoming chapters in this book feature many of the standard modules that are specific to the web, systems, databases, and so on. In this section, I talk about some standard modules that have generic uses.

Handle Missing Keys with setdefault() and defaultdict()

You’ve seen that trying to access a dictionary with a nonexistent key raises an exception. Using the dictionary get() function to return a default value avoids an exception. The setdefault() function is like get(), but also assigns an item to the dictionary if the key is missing:

>>> periodic_table = {'Hydrogen': 1, 'Helium': 2}

>>> periodic_table

{'Hydrogen': 1, 'Helium': 2}

If the key was not already in the dictionary, the new value is used:

>>> carbon = periodic_table.setdefault('Carbon', 12)

>>> carbon

12

>>> periodic_table

{'Hydrogen': 1, 'Helium': 2, 'Carbon': 12}

If we try to assign a different default value to an existing key, the original value is returned and nothing is changed:

>>> helium = periodic_table.setdefault('Helium', 947)

>>> helium

2

>>> periodic_table

{'Hydrogen': 1, 'Helium': 2, 'Carbon': 12}

defaultdict() is similar, but specifies the default value for any new key up front, when the dictionary is created. Its argument is a function. In this example, we pass the function int, which will be called as int() and return the integer 0 :

>>> from collections import defaultdict

>>> periodic_table = defaultdict(int)

Now any missing value will be an integer (int), with the value 0 :

>>> periodic_table['Hydrogen'] = 1

>>> periodic_table['Lead']

0

>>> periodic_table

defaultdict(<class 'int'>, {'Hydrogen': 1, 'Lead': 0})

The argument to defaultdict() is a function that returns the value to be assigned to a missing key. In the following example, no_idea() is executed to return a value when needed:

>>> from collections import defaultdict

>>>

>>> def no_idea():

... return 'Huh?'

...

>>> bestiary = defaultdict(no_idea)

>>> bestiary['A'] = 'Abominable Snowman'

>>> bestiary['B'] = 'Basilisk'

>>> bestiary['A']

'Abominable Snowman'

>>> bestiary['B']

'Basilisk'

>>> bestiary['C']

'Huh?'

You can use the functions int(), list(), or dict() to return default empty values for those types: int() returns 0 , list() returns an empty list ([]), and dict() returns an empty dictionary ({}). If you omit the argument, the initial value of a new key will be set to None.

By the way, you can use lambda to define your default-making function right inside the call:

>>> bestiary = defaultdict( lambda : 'Huh?')

>>> bestiary['E']

'Huh?'

Using int is one way to make your own counter:

>>> from collections import defaultdict

>>> food_counter = defaultdict(int)

>>> for food in ['spam', 'spam', 'eggs', 'spam']:

... food_counter[food] += 1

>>> for food, count in food_counter.items():

... print (food, count)

eggs 1

spam 3

In the preceding example, if food_counter had been a normal dictionary instead of a defaultdict, Python would have raised an exception every time we tried to increment the dictionary element food_counter[food] because it would not have been initialized. We would have needed to do some extra work, as shown here:

>>> dict_counter = {}

>>> for food in ['spam', 'spam', 'eggs', 'spam']:

... if not food in dict_counter:

... dict_counter[food] = 0

... dict_counter[food] += 1

>>> for food, count in dict_counter.items():

... print (food, count)

spam 3

eggs 1

Count Items with Counter()

Speaking of counters, the standard library has one that does the work of the previous

example and more:

>>> from collections import Counter

>>> breakfast = ['spam', 'spam', 'eggs', 'spam']

>>> breakfast_counter = Counter(breakfast)

>>> breakfast_counter

Counter({'spam': 3, 'eggs': 1})

The most_common() function returns all elements in descending order, or just the top count elements if given a count:

>>> breakfast_counter.most_common()

[('spam', 3), ('eggs', 1)]

>>> breakfast_counter.most_common(1)

[('spam', 3)]

You can combine counters. First, let’s see again what’s in breakfast_counter:

>>> breakfast_counter

>>> Counter({'spam': 3, 'eggs': 1})

This time, we make a new list called lunch, and a counter called lunch_counter:

>>> lunch = ['eggs', 'eggs', 'bacon']

>>> lunch_counter = Counter(lunch)

>>> lunch_counter

Counter({'eggs': 2, 'bacon': 1})

The first way we combine the two counters is by addition, using +:

>>> breakfast_counter + lunch_counter

Counter({'spam': 3, 'eggs': 3, 'bacon': 1})

As you might expect, you subtract one counter from another by using -. What’s for breakfast but not for lunch?

>>> breakfast_counter - lunch_counter

Counter({'spam': 3})

Okay, now what can we have for lunch that we can’t have for breakfast?

>>> lunch_counter - breakfast_counter

Counter({'bacon': 1, 'eggs': 1})

Similar to sets in Chapter 8, you can get common items by using the intersection operator &:

>>> breakfast_counter & lunch_counter

Counter({'eggs': 1})

The intersection chose the common element (‘eggs’) with the lower count. This makes sense: breakfast offered only one egg, so that’s the common count.

| Finally, you can get all items by using the union operator | : |

>>> breakfast_counter | lunch_counter

Counter({'spam': 3, 'eggs': 2, 'bacon': 1})

The item ‘eggs’ was again common to both. Unlike addition, union didn’t add their counts, but selected the one with the larger count.

Order by Key with OrderedDict()

This is an example run with the Python 2 interpreter:

>>> quotes = {

... 'Moe': 'A wise guy, huh?',

... 'Larry': 'Ow!',

... 'Curly': 'Nyuk nyuk!',

... }

>>> for stooge in quotes:

... print (stooge)

Larry

Curly

Moe

Starting with Python 3.7, dictionaries retain keys in the order in which they were added. OrderedDict is useful for earlier versions, which have an unpredictable order. The examples in this section are relevant only if you’re a version of Python earlier than 3.7.

An OrderedDict() remembers the order of key addition and returns them in the same order from an iterator. Try creating an OrderedDict from a sequence of (key, value) tuples:

>>> from collections import OrderedDict

>>> quotes = OrderedDict([

... ('Moe', 'A wise guy, huh?'),

... ('Larry', 'Ow!'),

... ('Curly', 'Nyuk nyuk!'),

... ])

>>>

>>> for stooge in quotes:

... print (stooge)

Moe

Larry

Curly

Stack + Queue == deque

A deque (pronounced deck) is a double-ended queue, which has features of both a stack and a queue. It’s useful when you want to add and delete items from either end of a sequence. Here, we work from both ends of a word to the middle to see whether it’s a palindrome. The function popleft() removes the leftmost item from the deque and returns it; pop() removes the rightmost item and returns it. Together, they work from the ends toward the middle. As long as the end characters match, it keeps popping until it reaches the middle:

>>> def palindrome(word):

... from collections import deque

... dq = deque(word)

... while len(dq) > 1:

... if dq.popleft() != dq.pop():

... return False

... return True

>>> palindrome('a')

True

>>> palindrome('racecar')

True

>>> palindrome('')

True

>>> palindrome('radar')

True

>>> palindrome('halibut')

False

I used this as a simple illustration of deques. If you really wanted a quick palindrome checker, it would be a lot simpler to just compare a string with its reverse. Python doesn’t have a reverse() function for strings, but it does have a way to reverse a string with a slice, as illustrated here:

>>> def another_palindrome(word):

... return word == word[::-1]

>>> another_palindrome('radar')

True

>>> another_palindrome('halibut')

False

Iterate over Code Structures with itertools

itertools contains special-purpose iterator functions. Each returns one item at a time when called within a for … in loop, and remembers its state between calls. chain() runs through its arguments as though they were a single iterable:

>>> import itertools

>>> for item in itertools.chain([1, 2], ['a', 'b']):

... print (item)

...

1

2

a

b

cycle() is an infinite iterator, cycling through its arguments:

>>> import itertools

>>> for item in itertools.cycle([1, 2]):

... print (item)

1 2 1 2...

And, so on.

accumulate() calculates accumulated values. By default, it calculates the sum:

>>> import itertools

>>> for item in itertools.accumulate([1, 2, 3, 4]):

... print (item)

1

3

6

10

You can provide a function as the second argument to accumulate(), and it will be used instead of addition. The function should take two arguments and return a single result. This example calculates an accumulated product:

>>> import itertools

>>> def multiply(a, b):

... return a * b

>>> for item in itertools.accumulate([1, 2, 3, 4], multiply):

... print (item)

1

2

6

24

The itertools module has many more functions, notably some for combinations and permutations that can be time savers when the need arises.

Print Nicely with pprint()

All of our examples have used print() (or just the variable name, in the interactive interpreter) to print things. Sometimes, the results are hard to read. We need a pretty printer such as pprint():

>>> from pprint import pprint

>>> quotes = OrderedDict([

... ('Moe', 'A wise guy, huh?'),

... ('Larry', 'Ow!'),

... ('Curly', 'Nyuk nyuk!'),

... ])

>>>

Plain old print() just dumps things out there:

>>> print (quotes)

OrderedDict([('Moe', 'A wise guy, huh?'), ('Larry', 'Ow!'),

('Curly', 'Nyuk nyuk!')])

However, pprint() tries to align elements for better readability:

>>> pprint(quotes)

{'Moe': 'A wise guy, huh?',

'Larry': 'Ow!',

'Curly': 'Nyuk nyuk!'}

Get Random

We played with random.choice() at the beginning of this chapter. That returns a value from the sequence (list, tuple, dictionary, string) argument that it’s given:

>>> from random import choice

>>> choice([23, 9, 46, 'bacon', 0x123abc])

1194684

>>> choice( ('a', 'one', 'and-a', 'two') )

'one'

>>> choice(range(100))

68

>>> choice('alphabet')

'l'

Use the sample() function to get more than one value at a time:

>>> from random import sample

>>> sample([23, 9, 46, 'bacon', 0x123abc], 3)

[1194684, 23, 9]

>>> sample(('a', 'one', 'and-a', 'two'), 2)

['two', 'and-a']

>>> sample(range(100), 4)

[54, 82, 10, 78]

>>> sample('alphabet', 7)

['l', 'e', 'a', 't', 'p', 'a', 'b']

To get a random integer from any range, you can use choice() or sample() with range(), or use randint() or randrange():

>>> from random import randint

>>> randint(38, 74)

71

>>> randint(38, 74)

60

>>> randint(38, 74)

61

randrange(), like range(), has arguments for the start (inclusive) and end (exclusive) integers, and an optional integer step:

>>> from random import randrange

>>> randrange(38, 74)

65

>>> randrange(38, 74, 10)

68

>>> randrange(38, 74, 10)

48

Finally, get a random real number (a float) between 0.0 and 1.0:

>>> from random import random

>>> random()

0.07193393312692198

>>> random()

0.7403243673826271

>>> random()

0.9716517846775018

More Batteries: Get Other Python Code

Sometimes, the standard library doesn’t have what you need, or doesn’t do it in quite the right way. There’s an entire world of open source, third-party Python software.

Good resources include the following:

- PyPi (also known as the Cheese Shop, after an old Monty Python skit)

- GitHub

- readthedocs

You can find many smaller code examples at activestate.

Almost all of the Python code in this book uses the standard Python installation on your computer, which includes all the built-ins and the standard library. External packages are featured in some places: I mentioned requests in Chapter 1; I have more details in Chapter 18. Appendix B shows how to install third-party Python software, along with many other nuts-and-bolts development details.

Coming Up

The next chapter is a practical one, covering many aspects of data manipulation in Python. You’ll encounter the binary bytes and bytearray data types, handle Unicode characters in text strings, and search text strings with regular expressions.

Things to Do

11.1 Create a file called zoo.py. In it, define a function called hours() that prints the string ‘Open 9-5 daily’. Then, use the interactive interpreter to import the zoo module and call its hours() function.

11.2 In the interactive interpreter, import the zoo module as menagerie and call its hours() function.

11.3 Staying in the interpreter, import the hours() function from zoo directly and call it.

11.4 Import the hours() function as info and call it.

11.5 Make a dictionary called plain with the key-value pairs ‘a’: 1, ‘b’: 2, and ‘c’: 3, and then print it.

11.6 Make an OrderedDict called fancy from the same pairs listed in the previous question and print it. Did it print in the same order as plain?

11.7 Make a defaultdict called dict_of_lists and pass it the argument list. Make the list dict_of_lists[‘a’] and append the value ‘something for a’ to it in one assignment. Print dict_of_lists[‘a’].