7장 Tuples and Lists

Table of contents

- Tuples

- Lists

- Create with []

- Create from a String with split()

- Get an Item by [ offset ]

- Get Items with a Slice

- Add an Item to the End with append()

- Add an Item by Offset with insert()

- Duplicate All Items with *

- Combine Lists by Using extend() or +

- Change an Item by [ offset ]

- Change Items with a Slice

- Delete an Item by Offset with del

- Delete an Item by Value with remove()

- Get an Item by Offset and Delete It with pop()

- Delete All Items with clear()

- Find an Item’s Offset by Value with index()

- Test for a Value with in

- Count Occurrences of a Value with count()

- Convert a List to a String with join()

- Reorder Items with sort() or sorted()

- Get Length with len()

- Assign with =

- Copy with copy(), list(), or a Slice

- Copy Everything with deepcopy()

- Compare Lists

- Iterate with for and in

- Iterate Multiple Sequences with zip()

- Create a List with a Comprehension

- Lists of Lists

- Tuples Versus Lists

- There Are No Tuple Comprehensions

- Coming Up

- Things to Do

- list 요약

- for 반복문으로 리스트 만들기

In the previous chapters, we started with some of Python’s basic data types: booleans,

integers, floats, and strings. If you think of those as atoms, the data structures in this

chapter are like molecules. That is, we combine those basic types in more complex

ways. You will use these every day. Much of programming consists of chopping and

gluing data into specific forms, and these are your hacksaws and glue guns.

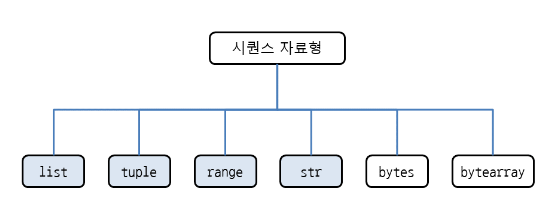

Most computer languages can represent a sequence of items indexed by their integer

position: first, second, and so on down to the last. You’ve already seen Python strings,

which are sequences of characters.

Python has two other sequence structures: tuples and lists. These contain zero or

more elements. Unlike strings, the elements can be of different types. In fact, each ele‐

ment can be any Python object. This lets you create structures as deep and complex as

you like.

Why does Python contain both lists and tuples? Tuples are immutable; when you

assign elements (only once) to a tuple, they’re baked in the cake and can’t be changed.

Lists are mutable, meaning you can insert and delete elements with great enthusiasm.

I’ll show many examples of each, with an emphasis on lists.

Tuples

Let’s get one thing out of the way first. You may hear two different pronunciations for

tuple. Which is right? If you guess wrong, do you risk being considered a Python

poseur? No worries. Guido van Rossum, the creator of Python, said via Twitter:

I pronounce tuple too-pull on Mon/Wed/Fri and tub-pull on Tue/Thu/Sat. On Sunday

I don’t talk about them. :)

Create with Commas and ()

The syntax to make tuples is a little inconsistent, as the following examples demon‐

strate. Let’s begin by making an empty tuple using ():

>>> empty_tuple = ()

>>> empty_tuple

()

To make a tuple with one or more elements, follow each element with a comma. This

works for one-element tuples:

>>> one_marx = 'Groucho',

>>> one_marx

('Groucho',)

You could enclose them in parentheses and still get the same tuple:

>>> one_marx = ('Groucho',)

>>> one_marx

('Groucho',)

Here’s a little gotcha: if you have a single thing in parentheses and omit that comma,

you would not get a tuple, but just the thing (in this example, the string ‘Groucho’):

>>> one_marx = ('Groucho')

>>> one_marx

'Groucho'

>>> type(one_marx)

<class 'str'>

If you have more than one element, follow all but the last one with a comma:

>>> marx_tuple = 'Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo'

>>> marx_tuple

('Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo')

Python includes parentheses when echoing a tuple. You often don’t need them when

you define a tuple, but using parentheses is a little safer, and it helps to make the tuple

more visible:

>>> marx_tuple = ('Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo')

>>> marx_tuple

('Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo')

You do need the parentheses for cases in which commas might also have another use.

In this example, you can create and assign a single-element tuple with just a trailing

comma, but you can’t pass it as an argument to a function:

>>> one_marx = 'Groucho',

>>> type(one_marx)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> type('Groucho',)

<class 'str'>

>>> type(('Groucho',))

<class 'tuple'>

Tuples let you assign multiple variables at once:

>>> marx_tuple = ('Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo')

>>> a, b, c = marx_tuple

>>> a

'Groucho'

>>> b

'Chico'

>>> c

'Harpo'

This is sometimes called tuple unpacking.

You can use tuples to exchange values in one statement without using a temporary

variable:

>>> password = 'swordfish'

>>> icecream = 'tuttifrutti'

>>> password, icecream = icecream, password

>>> password

'tuttifrutti'

>>> icecream

'swordfish'

>>>

Create with tuple()

The tuple() conversion function makes tuples from other things:

>>> marx_list = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> tuple(marx_list)

('Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo')

Combine Tuples by Using +

This is similar to combining strings:

>>> ('Groucho',) + ('Chico', 'Harpo')

('Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo')

Duplicate Items with *

This is like repeated use of +:

>>> ('yada',) * 3

('yada', 'yada', 'yada')

Compare Tuples

This works much like list comparisons:

>>> a = (7, 2)

>>> b = (7, 2, 9)

>>> a == b

False

>>> a <= b

True

>>> a < b

True

Iterate with for and in

Tuple iteration is like iteration of other types:

>>> words = ('fresh','out', 'of', 'ideas')

>>> for word in words:

... print (word)

fresh

out

of

ideas

Modify a Tuple

You can’t! Like strings, tuples are immutable, so you can’t change an existing one. As

you saw just before, you can concatenate (combine) tuples to make a new one, as you

can with strings:

>>> t1 = ('Fee', 'Fie', 'Foe')

>>> t2 = ('Flop,')

>>> t1 + t2

('Fee', 'Fie', 'Foe', 'Flop')

This means that you can appear to modify a tuple like this:

>>> t1 = ('Fee', 'Fie', 'Foe')

>>> t2 = ('Flop,')

>>> t1 += t2

>>> t1

('Fee', 'Fie', 'Foe', 'Flop')

But it isn’t the same t1. Python made a new tuple from the original tuples pointed to

by t1 and t2, and assigned the name t1 to this new tuple. You can see with id()

when a variable name is pointing to a new value:

>>> t1 = ('Fee', 'Fie', 'Foe')

>>> t2 = ('Flop',)

>>> id(t1)

4365405712

>>> t1 += t2

>>> id(t1)

4364770744

Lists

Lists are good for keeping track of things by their order, especially when the order

and contents might change. Unlike strings, lists are mutable. You can change a list in

place, add new elements, and delete or replace existing elements. The same value can

occur more than once in a list.

Create with []

A list is made from zero or more elements, separated by commas and surrounded by

square brackets:

>>> empty_list = [ ]

>>> weekdays = ['Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday']

>>> big_birds = ['emu', 'ostrich', 'cassowary']

>>> first_names = ['Graham', 'John', 'Terry', 'Terry', 'Michael']

>>> leap_years = [2000, 2004, 2008]

>>> randomness = ['Punxsatawney", {"groundhog": "Phil"}, "Feb. 2"}

The first_names list shows that values do not need to be unique.

If you want to keep track of only unique values and don’t care about order, a Python set might be a better choice than a list. In the previous example, big_birds could have been a set. We explore sets in Chapter 8.

### Create or Convert with list()

You can also make an empty list with the list() function:

another_empty_list = list() another_empty_list [] ```

Python’s list() function also converts other iterable data types (such as tuples,

strings, sets, and dictionaries) to lists. The following example converts a string to a list

of one-character strings:

>>> list('cat')

['c', 'a', 't']

This example converts a tuple to a list:

>>> a_tuple = ('ready', 'fire', 'aim')

>>> list(a_tuple)

['ready', 'fire', 'aim']

Create from a String with split()

As I mentioned earlier in “Split with split()” on page 72 , use split() to chop a string

into a list by some separator:

>>> talk_like_a_pirate_day = '9/19/2019'

>>> talk_like_a_pirate_day.split('/')

['9', '19', '2019']

What if you have more than one separator string in a row in your original string?

Well, you get an empty string as a list item:

>>> splitme = 'a/b//c/d///e'

>>> splitme.split('/')

['a', 'b', '', 'c', 'd', '', '', 'e']

If you had used the two-character separator string //, instead, you would get this:

>>> splitme = 'a/b//c/d///e'

>>> splitme.split('//')

>>>

['a/b', 'c/d', '/e']

Get an Item by [ offset ]

As with strings, you can extract a single value from a list by specifying its offset:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes[0]

'Groucho'

>>> marxes[1]

'Chico'

>>> marxes[2]

'Harpo'

Again, as with strings, negative indexes count backward from the end:

>>> marxes[-1]

'Harpo'

>>> marxes[-2]

'Chico'

>>> marxes[-3]

'Groucho'

>>>

The offset has to be a valid one for this list—a position you have

assigned a value previously. If you specify an offset before the

beginning or after the end, you’ll get an exception (error). Here’s

what happens if we try to get the sixth Marx brother (offset 5

counting from 0 ), or the fifth before the end:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes[5]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

IndexError: list index out of range

>>> marxes[-5]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

IndexError: list index out of range

Get Items with a Slice

You can extract a subsequence of a list by using a slice:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes[0:2]

['Groucho', 'Chico']

A slice of a list is also a list.

As with strings, slices can step by values other than one. The next example starts at

the beginning and goes right by 2:

>>> marxes[::2]

['Groucho', 'Harpo']

Here, we start at the end and go left by 2:

>>> marxes[::-2]

['Harpo', 'Groucho']

And finally, the trick to reverse a list:

>>> marxes[::-1]

['Harpo', 'Chico', 'Groucho']

None of these slices changed the marxes list itself, because we didn’t assign them to

marxes. To reverse a list in place, use list .reverse():

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes.reverse()

>>> marxes

['Harpo', 'Chico', 'Groucho']

The reverse() function changes the list but doesn’t return its

value.

As you saw with strings, a slice can specify an invalid index, but will not cause an

exception. It will “snap” to the closest valid index or return nothing:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes[4:]

[]

>>> marxes[-6:]

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes[-6:-2]

['Groucho']

>>> marxes[-6:-4]

[]

Add an Item to the End with append()

The traditional way of adding items to a list is to append() them one by one to the

end. In the previous examples, we forgot Zeppo, but that’s alright because the list is

mutable, so we can add him now:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes.append('Zeppo')

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo']

Add an Item by Offset with insert()

The append() function adds items only to the end of the list. When you want to add

an item before any offset in the list, use insert(). Offset 0 inserts at the beginning.

An offset beyond the end of the list inserts at the end, like append(), so you don’t

need to worry about Python throwing an exception:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes.insert(2, 'Gummo')

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Gummo', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes.insert(10, 'Zeppo')

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Gummo', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo']

Duplicate All Items with *

In Chapter 5, you saw that you can duplicate a string’s characters with *. The same

works for a list:

>>> ["blah"] * 3

['blah', 'blah', 'blah']

Combine Lists by Using extend() or +

You can merge one list into another by using extend(). Suppose that a well-meaning

person gave us a new list of Marxes called others, and we’d like to merge them into

the main marxes list:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo']

>>> others = ['Gummo', 'Karl']

>>> marxes.extend(others)

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo', 'Gummo', 'Karl']

Alternatively, you can use + or +=:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo']

>>> others = ['Gummo', 'Karl']

>>> marxes += others

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo', 'Gummo', 'Karl']

If we had used append(), others would have been added as a single list item rather

than merging its items:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo']

>>> others = ['Gummo', 'Karl']

>>> marxes.append(others)

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo', ['Gummo', 'Karl']]

This again demonstrates that a list can contain elements of different types. In this

case, four strings, and a list of two strings.

Change an Item by [ offset ]

Just as you can get the value of a list item by its offset, you can change it:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes[2] = 'Wanda'

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Wanda']

Again, the list offset needs to be a valid one for this list.

You can’t change a character in a string in this way, because strings are immutable.

Lists are mutable. You can change how many items a list contains as well as the items

themselves.

Change Items with a Slice

The previous section showed how to get a sublist with a slice. You can also assign val‐

ues to a sublist with a slice:

>>> numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> numbers[1:3] = [8, 9]

>>> numbers

[1, 8, 9, 4]

The righthand thing that you’re assigning to the list doesn’t even need to have the

same number of elements as the slice on the left:

>>> numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> numbers[1:3] = [7, 8, 9]

>>> numbers

[1, 7, 8, 9, 4]

>>> numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> numbers[1:3] = []

>>> numbers

[1, 4]

Actually, the righthand thing doesn’t even need to be a list. Any Python iterable will

do, separating its items and assigning them to list elements:

>>> numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> numbers[1:3] = (98, 99, 100)

>>> numbers

[1, 98, 99, 100, 4]

>>> numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> numbers[1:3] = 'wat?'

>>> numbers

[1, 'w', 'a', 't', '?', 4]

Delete an Item by Offset with del

Our fact checkers have just informed us that Gummo was indeed one of the Marx

Brothers, but Karl wasn’t, and that whoever inserted him earlier was very rude. Let’s

fix that:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Gummo', 'Karl']

>>> marxes[-1]

'Karl'

>>> del marxes[-1]

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Gummo']

When you delete an item by its position in the list, the items that follow it move back

to take the deleted item’s space, and the list’s length decreases by one. If we deleted

‘Chico’ from the last version of the marxes list, we get this as a result:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Gummo']

>>> del marxes[1]

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Harpo', 'Gummo']

del is a Python statement, not a list method—you don’t say

marxes[-1].del(). It’s sort of the reverse of assignment (=): it

detaches a name from a Python object and can free up the object’s

memory if that name were the last reference to it.

Delete an Item by Value with remove()

If you’re not sure or don’t care where the item is in the list, use remove() to delete it

by value. Goodbye, Groucho:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes.remove('Groucho')

>>> marxes

['Chico', 'Harpo']

If you had duplicate list items with the same value, remove() deletes only the first one

it finds.

Get an Item by Offset and Delete It with pop()

You can get an item from a list and delete it from the list at the same time by using

pop(). If you call pop() with an offset, it will return the item at that offset; with no

argument, it uses -1. So, pop(0) returns the head (start) of the list, and pop() or

pop(-1) returns the tail (end), as shown here:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo']

>>> marxes.pop()

'Zeppo'

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes.pop(1)

'Chico'

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Harpo']

It’s computing jargon time! Don’t worry, these won’t be on the final

exam. If you use append() to add new items to the end and pop()

to remove them from the same end, you’ve implemented a data

structure known as a LIFO (last in, first out) queue. This is more

commonly known as a stack. pop(0) would create a FIFO (first in,

first out) queue. These are useful when you want to collect data as

they arrive and work with either the oldest first (FIFO) or the new‐

est first (LIFO).

Delete All Items with clear()

Python 3.3 introduced a method to clear a list of all its elements:

>>> work_quotes = ['Working hard?', 'Quick question!', 'Number one priorities!']

>>> work_quotes

['Working hard?', 'Quick question!', 'Number one priorities!']

>>> work_quotes.clear()

>>> work_quotes

[]

Find an Item’s Offset by Value with index()

If you want to know the offset of an item in a list by its value, use index():

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo']

>>> marxes.index('Chico')

1

If the value is in the list more than once, only the offset of the first one is returned:

>>> simpsons = ['Lisa', 'Bart', 'Marge', 'Homer', 'Bart']

>>> simpsons.index('Bart')

1

Test for a Value with in

The Pythonic way to check for the existence of a value in a list is using in:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo', 'Zeppo']

>>> 'Groucho' in marxes

True

>>> 'Bob' in marxes

False

The same value may be in more than one position in the list. As long as it’s in there at

least once, in will return True:

>>> words = ['a', 'deer', 'a' 'female', 'deer']

>>> 'deer' in words

True

If you check for the existence of some value in a list often and don’t

care about the order of items, a Python set is a more appropriate

way to store and look up unique values. We talk about sets in

Chapter 8.

Count Occurrences of a Value with count()

To count how many times a particular value occurs in a list, use count():

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marxes.count('Harpo')

1

>>> marxes.count('Bob')

0

>>> snl_skit = ['cheeseburger', 'cheeseburger', 'cheeseburger']

>>> snl_skit.count('cheeseburger')

3

Convert a List to a String with join()

“Combine by Using join()” on page 73 discussed join() in greater detail, but here’s

another example of what you can do with it:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> ', '.join(marxes)

'Groucho, Chico, Harpo'

You might be thinking that this seems a little backward. join() is a string method,

not a list method. You can’t say marxes.join(‘, ‘), even though it seems more intu‐

itive. The argument to join() is a string or any iterable sequence of strings (includ‐

ing a list), and its output is a string. If join() were just a list method, you couldn’t use

it with other iterable objects such as tuples or strings. If you did want it to work with

any iterable type, you’d need special code for each type to handle the actual joining. It

might help to remember—join() is the opposite of split(), as shown here:

>>> friends = ['Harry', 'Hermione', 'Ron']

>>> separator = ' * '

>>> joined = separator.join(friends)

>>> joined

'Harry * Hermione * Ron'

>>> separated = joined.split(separator)

>>> separated

['Harry', 'Hermione', 'Ron']

>>> separated == friends

True

Reorder Items with sort() or sorted()

You’ll often need to sort the items in a list by their values rather than their offsets.

Python provides two functions:

- The list method sort() sorts the list itself, in place.

- The general function sorted() returns a sorted copy of the list.

If the items in the list are numeric, they’re sorted by default in ascending numeric

order. If they’re strings, they’re sorted in alphabetical order:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> sorted_marxes = sorted(marxes)

>>> sorted_marxes

['Chico', 'Groucho', 'Harpo']

sorted_marxes is a new list, and creating it did not change the original list:

>>> marxes

['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

But calling the list function sort() on the marxes list does change marxes:

>>> marxes.sort()

>>> marxes

['Chico', 'Groucho', 'Harpo']

If the elements of your list are all of the same type (such as strings in marxes), sort()

will work correctly. You can sometimes even mix types—for example, integers and

floats—because they are automatically converted to one another by Python in

expressions:

>>> numbers = [2, 1, 4.0, 3]

>>> numbers.sort()

>>> numbers

[1, 2, 3, 4.0]

The default sort order is ascending, but you can add the argument reverse=True to

set it to descending:

>>> numbers = [2, 1, 4.0, 3]

>>> numbers.sort(reverse=True)

>>> numbers

[4.0, 3, 2, 1]

Get Length with len()

len() returns the number of items in a list:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> len(marxes)

3

Assign with =

When you assign one list to more than one variable, changing the list in one place

also changes it in the other, as illustrated here:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> a

[1, 2, 3]

>>> b = a

>>> b

[1, 2, 3]

>>> a[0] = 'surprise'

>>> a

['surprise', 2, 3]

So what’s in b now? Is it still [1, 2, 3], or [‘surprise’, 2, 3]? Let’s see:

>>> b

['surprise', 2, 3]

Remember the box (object) and string with note (variable name) analogy in Chap‐

ter 2? b just refers to the same list object as a (both name strings lead to the same

object box). Whether we change the list contents by using the name a or b, it’s reflec‐

ted in both:

>>> b

['surprise', 2, 3]

>>> b[0] = 'I hate surprises'

>>> b

['I hate surprises', 2, 3]

>>> a

['I hate surprises', 2, 3]

Copy with copy(), list(), or a Slice

You can copy the values of a list to an independent, fresh list by using any of these methods:

- The list copy() method

- The list() conversion function

- The list slice [:]

Our original list will be a again. We make b with the list copy() function, c with the list() conversion function, and d with a list slice:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = a.copy()

>>> c = list(a)

>>> d = a[:]

Again, b, c, and d are copies of a: they are new objects with their own values and no connection to the original list object [1, 2, 3] to which a refers. Changing a does not affect the copies b, c, and d:

>>> a[0] = 'integer lists are boring'

>>> a

['integer lists are boring', 2, 3]

>>> b

[1, 2, 3]

>>> c

[1, 2, 3]

>>> d

[1, 2, 3]

Copy Everything with deepcopy()

The copy() function works well if the list values are all immutable. As you’ve seen before, mutable values (like lists, tuples, or dicts) are references. A change in the original or the copy would be reflected in both.

Let’s use the previous example but make the last element in list a the list [8, 9] instead of the integer 3 :

>>> a = [1, 2, [8, 9]]

>>> b = a.copy()

>>> c = list(a)

>>> d = a[:]

>>> a

[1, 2, [8, 9]]

>>> b

[1, 2, [8, 9]]

>>> c

[1, 2, [8, 9]]

>>> d

[1, 2, [8, 9]]

So far, so good. Now change an element in that sublist in a:

>>> a[2][1] = 10

>>> a

[1, 2, [8, 10]]

>>> b

[1, 2, [8, 10]]

>>> c

[1, 2, [8, 10]]

>>> d

[1, 2, [8, 10]]

The value of a[2] is now a list, and its elements can be changed. All the list-copying methods we used were shallow (not a value judgment, just a depth one).

To fix this, we need to use the deepcopy() function:

>>> import copy

>>> a = [1, 2, [8, 9]]

>>> b = copy.deepcopy(a)

>>> a

[1, 2, [8, 9]]

>>> b

[1, 2, [8, 9]]

>>> a[2][1] = 10

>>> a

[1, 2, [8, 10]]

>>> b

[1, 2, [8, 9]]

deepcopy() can handle deeply nested lists, dictionaries, and other objects.

You’ll read more about import in Chapter 9.

Compare Lists

You can directly compare lists with the comparison operators like ==, <, and so on.

The operators walk through both lists, comparing elements at the same offsets. If list a is shorter than list b, and all of its elements are equal, a is less than b:

>>> a = [7, 2]

>>> b = [7, 2, 9]

>>> a == b

False

>>> a <= b

True

>>> a < b

True

Iterate with for and in

In Chapter 6, you saw how to iterate over a string with for, but it’s much more common to iterate over lists:

>>> cheeses = ['brie', 'gjetost', 'havarti']

>>> for cheese in cheeses:

... print (cheese)

...

brie

gjetost

havarti

As before, break ends the for loop and continue steps to the next iteration:

>>> cheeses = ['brie', 'gjetost', 'havarti']

>>> for cheese in cheeses:

... if cheese.startswith('g'):

... print ("I won't eat anything that starts with 'g'")

... break

... else :

... print (cheese)

...

brie

I won't eat anything that starts with 'g'

You can still use the optional else if the for completed without a break:

>>> cheeses = ['brie', 'gjetost', 'havarti']

>>> for cheese in cheeses:

... if cheese.startswith('x'):

... print ("I won't eat anything that starts with 'x'")

... break

... else :

... print (cheese)

... else :

... print ("Didn't find anything that started with 'x'")

brie

gjetost

havarti

Didn't find anything that started with 'x'

If the initial for never ran, control goes to the else also:

>>> cheeses = []

>>> for cheese in cheeses:

... print ('This shop has some lovely', cheese)

... break

... else : # no break means no cheese

... print ('This is not much of a cheese shop, is it?')

This is not much of a cheese shop, is it?

Because the cheeses list was empty in this example, for cheese in cheeses never completed a single loop and its break statement was never executed.

Iterate Multiple Sequences with zip()

There’s one more nice iteration trick: iterating over multiple sequences in parallel by

using the zip() function:

>>> days = ['Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday']

>>> fruits = ['banana', 'orange', 'peach']

>>> drinks = ['coffee', 'tea', 'beer']

>>> desserts = ['tiramisu', 'ice cream', 'pie', 'pudding']

>>> for day, fruit, drink, dessert in zip(days, fruits, drinks, desserts):

... print (day, ": drink", drink, "- eat", fruit, "- enjoy", dessert)

...

Monday : drink coffee - eat banana - enjoy tiramisu

Tuesday : drink tea - eat orange - enjoy ice cream

Wednesday : drink beer - eat peach - enjoy pie

동일한 offset에 있는 요소를 쌍지어 tuple을 생성한다.

zip() 는 가장 짧은 시컨스를 기준으로 생성된다.

>>> english = 'Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday'

>>> french = 'Lundi', 'Mardi', 'Mercredi'

# zip 자료형

a = zip(english, french)

print(type(a)) # <class 'zip'>

print(*a) # ('Monday', 'Lundi') ('Tuesday', 'Mardi') ('Wednesday', 'Mercredi')

# list화 결과

>>> list( zip(english, french) )

[('Monday', 'Lundi'), ('Tuesday', 'Mardi'), ('Wednesday', 'Mercredi')]

# dict화 결과

>>> dict( zip(english, french) )

{'Monday': 'Lundi', 'Tuesday': 'Mardi', 'Wednesday': 'Mercredi'}

Create a List with a Comprehension

[ expression for item in iterable ]

for/in iteration을 포함한 list comprehension : [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

# 방법1

>>> number_list = []

>>> number_list.append(1)

>>> number_list.append(2)

>>> number_list.append(3)

>>> number_list.append(4)

>>> number_list.append(5)

>>> number_list

# 방법2

>>> number_list = []

>>> for number in range(1, 6):

... number_list.append(number)

...

>>> number_list

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

# 방법3

>>> number_list = list(range(1, 6))

>>> number_list

# 방법4

>>> number_list = [number for number in range(1,6)]

>>> number_list

A list comprehension can include a conditional expression, looking something like this:

[ expression for item in iterable if condition ]

Let’s make a new comprehension that builds a list of only the odd numbers between 1 and 5 (remember that number % 2 is True for odd numbers and False for even numbers):

>>> a_list = [number for number in range(1,6) if number % 2 == 1]

>>> a_list

[1, 3, 5]

Now, the comprehension is a little more compact than its traditional counterpart:

>>> a_list = []

>>> for number in range(1,6):

... if number % 2 == 1:

... a_list.append(number)

...

>>> a_list

[1, 3, 5]

Finally, just as there can be nested loops, there can be more than one set of for … clauses in the corresponding comprehension. To show this, let’s first try a plain old nested loop and print the results:

>>> rows = range(1,4)

>>> cols = range(1,3)

>>> for row in rows:

... for col in cols:

... print (row, col)

...

1 1

1 2

2 1

2 2

3 1

3 2

# 동일 기능

>>> rows = range(1,4)

>>> cols = range(1,3)

>>> cells = [(row, col) for row in rows for col in cols]

>>> for cell in cells:

... print (*cell)

...

Lists of Lists

Lists can contain elements of different types, including other lists, as illustrated here:

>>> small_birds = ['hummingbird', 'finch']

>>> extinct_birds = ['dodo', 'passenger pigeon', 'Norwegian Blue']

>>> carol_birds = [3, 'French hens', 2, 'turtledoves']

>>> all_birds = [small_birds, extinct_birds, 'macaw', carol_birds]

...

>>> all_birds

[['hummingbird', 'finch'], ['dodo', 'passenger pigeon', 'Norwegian Blue'], 'macaw',

[3, 'French hens', 2, 'turtledoves']]

...

>>> all_birds[1]

['dodo', 'passenger pigeon', 'Norwegian Blue']

...

>>> all_birds[1][0]

'dodo'

The [1] refers to the list that’s the second item in all_birds, and the [0] refers to the first item in that inner list.

Tuples Versus Lists

tuple을 쓰는 이유?

- Tuples은 더 적은 공간을 이용한다.

- immutable 자료형이다.

- dictionary keys로 사용 가능하다.

- Named tuples은 objects의 대안이 될 수 있다.

I won’t go into much more detail about tuples here. In everyday programming, you’ll use lists and dictionaries more.

There Are No Tuple Comprehensions

Mutable types (lists, dictionaries, and sets)은 comprehensions을 갖는다.

Immutable types like strings and tuples need to be created with the other methods listed in their sections.

You might have thought that changing the square brackets of a list comprehension to parentheses would create a tuple comprehension. And it would appear to work because there’s no exception if you type this:

The thing between the parentheses is something else entirely: a generator comprehension, and it returns a generator object:

>>> number_thing = (number for number in range(1, 6))

>>> type(number_thing)

<class 'generator'>

I’ll get into generators in more detail in “Generators” on page 157. A generator is one way to provide data to an iterator.

Coming Up

They’re so swell, they get their own chapter: dictionaries and sets.

Things to Do

Use lists and tuples with numbers (Chapter 3) and strings (Chapter 5) to represent elements in the real world with great variety.

7.1 Create a list called years_list, starting with the year of your birth, and each year thereafter until the year of your fifth birthday. For example, if you were born in 1980, the list would be years_list = [1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985]. If you’re less than five years old and reading this book, I don’t know what to tell you.

def make_list(birth_year, old):

l =[birth_year+i for i in range(old+1)]

return l

L = make_list(1980,5)

print(L)

'''

[1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985]

'''

7.2 In which year in years_list was your third birthday? Remember, you were 0 years of age for your first year.

print(L[2]) # 1982

7.3 In which year in years_list were you the oldest?

print(L[-1]) # 1985

7.4 Make a list called things with these three strings as elements: “mozzarella”, “cinderella”, “salmonella”. 7.5 Capitalize the element in things that refers to a person and then print the list. Did it change the element in the list? 7.6 Make the cheesy element of things all uppercase and then print the list. 7.7 Delete the disease element from things, collect your Nobel Prize, and print the list.

#7-4

things = ["mozzarella", "cinderella", "salmonella"]

print(things) # ['mozzarella', 'cinderella', 'salmonella']

L = [i.title() for i in things]

print(L) # ['Mozzarella', 'Cinderella', 'Salmonella']

#7-5

person = things[1].title()

print(person) # Cinderella

print(things) # ['mozzarella', 'cinderella', 'salmonella']

#7-6

things[0] = things[0].upper()

print(things)

#7-7

del things[2]

print(things)

7.8 Create a list called surprise with the elements “Groucho”, “Chico”, and “Harpo”. 7.9 Lowercase the last element of the surprise list, reverse it, and then capitalize it.

#7.8

surprise = ["Groucho", "Chico", "Harpo"]

print(surprise)

#7.9 Lowercase the last element of the surprise list, reverse it, and then capitalize it.

surprise[-1] = surprise[-1].lower()

surprise[-1] = surprise[-1][::-1]

surprise[-1] = surprise[-1].capitalize()

print(surprise)

7.10 Use a list comprehension to make a list called even of the even numbers in range(10).

even = [i for i in range(10) if i%2 == 0]

print(even)

7.11 Let’s create a jump rope rhyme maker. You’ll print a series of two-line rhymes.

Start with this program fragment:

start1 = ["fee", "fie", "foe"]

rhymes = [

("flop", "get a mop"),

("fope", "turn the rope"),

("fa", "get your ma"),

("fudge", "call the judge"),

("fat", "pet the cat"),

("fog", "walk the dog"),

("fun", "say we're done"),

]

start2 = "Someone better"

For each tuple (first, second) in rhymes:

For the first line:

- Print each string in start1, capitalized and followed by an exclamation point and a space.

- Print first, also capitalized and followed by an exclamation point.

For the second line:

- Print start2 and a space.

- Print second and a period.

start1 = ["fee", "fie", "foe"]

rhymes = [

("flop", "get a mop"),

("fope", "turn the rope"),

("fa", "get your ma"),

("fudge", "call the judge"),

("fat", "pet the cat"),

("fog", "walk the dog"),

("fun", "say we're done"),

]

start2 = "Someone better"

for k in rhymes:

for i in start1:

print(i.capitalize(), '!',' ',sep="",end="")

print(k[0].capitalize(),'!',sep="")

print(start2," ",sep="",end="")

print(k[1],'.',sep="")

list 요약

리스트에 요소 추가하기

- append: 요소 하나를 추가

- extend(list): 리스트를 연결하여 확장

- insert(인덱스, 요소): 특정 인덱스에 요소 추가 ```python a = [10, 20, 30] a.append(500) print(a) # [10, 20, 30, 500]

a.append([500, 600]) print(a) # [10, 20, 30, 500, [500, 600]]

a = [10, 20, 30] a.extend([500, 600]) print(a) # [10, 20, 30, 500, 600]

a = [10, 20, 30] a.insert(2, 500) print(a) # [10, 20, 500, 30]

a = [10, 20, 30] a.insert(1, [500, 600]) print(a) # [10, [500, 600], 20, 30]

a = [10, 20, 30] a[1:2] = [500, 600] print(a) # [10, 500, 600]

### 리스트에서 요소 삭제하기

- pop(), pop(index): 마지막 요소 또는 특정 인덱스의 요소를 삭제

- remove(값): 특정 값을 찾아서 삭제

```python

a = [10, 20, 30]

a.pop()

print(a) # [10, 20]

a.pop(1)

print(a) # [10]

del a[0]

print(a) # []

a = [10, 20, 30,20]

a.remove(20)

print(a) # [10, 30, 20] - 앞의 20만 제거

리스트에서 특정 값의 인덱스 구하기

index(값)은 리스트에서 특정 값의 인덱스를 구합니다. 처음 찾은 인덱스를 구합니다(가장 작은 인덱스).

a = [10, 20, 30, 15, 20, 40]

result = a.index(20)

print(result) # 1

특정 값의 개수 구하기

count(값)은 리스트에서 특정 값의 개수를 구합니다.

a = [10, 20, 30, 15, 20, 40]

result = a.count(20)

print(result) # 2

리스트의 순서를 뒤집기

reverse()는 리스트에서 요소의 순서를 반대로 뒤집습니다.

a = [10, 20, 30, 15, 20, 40]

a.reverse()

print(a) # [40, 20, 15, 30, 20, 10]

리스트의 요소를 정렬하기

sort()는 리스트의 요소을 작은 순서대로 정렬합니다(오름차순) = sort(reverse=False)

a = [10, 20, 30, 15, 20, 40]

a.sort()

print(a) # [10, 15, 20, 20, 30, 40]

[참고] sort,reverse 메서드와 sorted, reversed 함수 차이

메서드는 리스트 자체 변경, _ed함수는 결과만 반환

리스트의 모든 요소를 삭제하기

clear()는 리스트의 모든 요소를 삭제합니다. = del a[:]

a = [10, 20, 30]

a.clear()

print(a) # [ ]

max, min, sum 구하기

리스트, 튜플에 적용

리스트를 슬라이스로 조작하기

리스트 끝에 리스트를 추가

a = [10, 20, 30]

a[len(a):] = [500]

print(a) # [10, 20, 30, 500]

리스트가 비어 있는지 확인하기 len 함수 이용 / 자체 / [-1] 이용

if not len(seq): # 리스트가 비어 있으면 True

if seq: # 리스트에 내용이 있으면 True

seq[-1] # 값 반환시 데이터 존재

list comprehension

- [식 for 변수 in 리스트]

- list(식 for 변수 in 리스트)

- [식 for 변수1 in 리스트1 if 조건식1 for 변수2 in 리스트2 if 조건식2

... for 변수n in 리스트n if 조건식n]

- list(식 for 변수1 in 리스트1 if 조건식1 for 변수2 in 리스트2 if 조건식2

... for 변수n in 리스트n if 조건식n)

- [(참일때 반환값) if 조건식 else (거짓일때 반환값) for 변수 in 리스트 if 조건식 ]

L = [22, 13, 45, 50, 98, 69, 43, 44, 1]

result = [True if x >= 50 else False for x in L]

print(result) # [False, False, False, True, True, True, False, False, False]

a = '97.xlsx 98.docx 99.docx 100.xlsx 101.docx 102.docx'

L = a.split()

result = [('0' * (3 - len(i.split('.')[0])) + i) if

(len(i.split('.')[0]) < 3) else i for i in L]

print(result)

# ['097.xlsx', '098.docx', '099.docx', '100.xlsx', '101.docx', '102.docx']

map 함수

a = list(map(str, range(10)))

print(a) # ['0', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7', '8', '9']

a = list(map(int, input().split()))

print(a) # [10, 20]

튜플에서 특정 값의 인덱스 구하기

index(값)은 튜플에서 특정 값의 인덱스를 구합니다.

a = (38, 21, 53, 62, 19, 53)

result = a.index(53)

print(result) # 2

특정 값의 개수 구하기

count(값)은 튜플에서 특정 값의 개수를 구합니다.

a = (10, 20, 30, 15, 20, 40)

resut = a.count(20)

print(result) # 2

튜플 표현식 사용하기

튜플을 리스트 표현식처럼 생성할 때는 다음과 같이 tuple 안에 for 반복문과 if 조건문을 지정합니다.

- tuple(식 for 변수 in 리스트 if 조건식)

[참고] ( )(괄호) 안에 표현식을 넣으면 튜플이 아니라 제너레이터 표현식이 됩니다.

for 반복문으로 리스트 만들기

a = [[0 for j in range(2)] for i in range(3)]

print(a) # [[0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0]]

a = [[0] * 2 for i in range(3)]

print(a) # [[0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0]]

a = [3, 1, 3, 2, 5] # 가로 크기를 저장한 리스트

b = [] # 빈 리스트 생성

for i in a: # 가로 크기를 저장한 리스트로 반복

line = [] # 안쪽 리스트로 사용할 빈 리스트 생성

for j in range(i): # 리스트 a에 저장된 가로 크기만큼 반복

line.append(0)

b.append(line) # 리스트 b에 안쪽 리스트를 추가

print(b) # [[0, 0, 0], [0], [0, 0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

a = [[0] * i for i in [3, 1, 3, 2, 5]]

print(a) # [[0, 0, 0], [0], [0, 0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

[참고] sorted로 2차원 리스트 정렬하기

2차원 리스트를 정렬할 때는 sorted 함수를 사용합니다.

sorted(반복가능한객체, key=정렬함수, reverse=True 또는 False)

다음은 학생 정보가 저장된 2차원 리스트를 정렬합니다.

students = [

['john', 'C', 19],

['maria', 'A', 25],

['andrew', 'B', 7]

]

print(sorted(students, key=lambda student: student[1])) # 안쪽 리스트의 인덱스 1을 기준으로 정렬

print(sorted(students, key=lambda student: student[2])) # 안쪽 리스트의 인덱스 2를 기준으로 정렬

실행 결과

[['maria', 'A', 25], ['andrew', 'B', 7], ['john', 'C', 19]]

[['andrew', 'B', 7], ['john', 'C', 19], ['maria', 'A', 25]]

sorted의 key에 정렬 함수를 지정하여 안쪽 리스트의 요소를 기준으로 정렬했습니다. student[1]은 안쪽 리스트의 인덱스 1을 뜻하며 'A', 'B', 'C' 순으로 정렬합니다. 마찬가지로 student[2]는 안쪽 리스트의 인덱스 2를 뜻하며 7, 19, 25 순으로 정렬합니다. 여기서는 정렬 함수를 람다 표현식으로 작성했다.