8장 Dictionaries and Sets

Table of contents

- Dictionaries

- Create with {}

- Create with dict()

- Convert with dict()

- Add or Change an Item by [ key ]

- Get an Item by [key] or with get()

- Get All keys with keys()

- Get All Values with values()

- Get All key-Value Pairs with items()

- Get Length with len()

- Combine Dictionaries with {a, b}

- Combine Dictionaries with update()

- Delete an Item by key with del

- Get an Item by key and Delete It with pop()

- Delete All Items with clear()

- Test for a key with in

- Assign with =

- Copy with copy()

- Copy Everything with deepcopy()

- Compare Dictionaries

- Iterate with for and in

- dictionary Comprehensions

- Sets

- Data Structures So Far

- Make Bigger Data Structures

- Coming Up

- Things to Do

- 딕셔너리 응용

Dictionaries

dictionary는 mutable 자료형이다.- set과 같이 순서가 없다.

- key 를 사용하여 value에 접근한다.

- key 는 immutable types(boolean, integer, float, tuple, string, and so on)이여야 한다.

In other languages, dictionaries might be called associative arrays,hashes, or hashmaps. In Python, a dictionary is also called a

dictto save syllables and make teenage boys snicker.

Create with {}

To create a dictionary, you place curly brackets ({}) around comma-separated key : value pairs. The simplest dictionary is an empty one, containing no keys or values at all:

>>> empty_dict = {}

>>> empty_dict

{}

Let’s make a small dictionary with quotes from Ambrose Bierce’s The Devil’s dictionary:

>>> bierce = {

... "day": "A period of twenty-four hours, mostly misspent",

... "positive": "Mistaken at the top of one's voice",

... "misfortune": "The kind of fortune that never misses",

... }

>>>

Typing the dictionary’s name in the interactive interpreter will print its keys and values:

>>> bierce

{'day': 'A period of twenty-four hours, mostly misspent',

'positive': "Mistaken at the top of one's voice",

'misfortune': 'The kind of fortune that never misses'}

In Python, it’s okay to leave a comma after the last item of a list, tuple, or dictionary. Also, you don’t need to indent, as I did in the preceding example, when you’re typing keys and *values* within the curly braces. It just helps readability.

Create with dict()

Some people don’t like typing so many curly brackets and quotes. You can also create a dictionary by passing named arguments and values to the dict() function.

The traditional way:

>>> acme_customer = {'first': 'Wile', 'middle': 'E', 'last': 'Coyote'}

>>> acme_customer

{'first': 'Wile', 'middle': 'E', 'last': 'Coyote'}

Using dict():

>>> acme_customer = dict(first="Wile", middle="E", last="Coyote")

>>> acme_customer

{'first': 'Wile', 'middle': 'E', 'last': 'Coyote'}

One limitation of the second way is that the argument names need to be legal variable names (no spaces, no reserved words):

>>> x = dict(name="Elmer", def="hunter")

File "<stdin>", line 1

x = dict(name="Elmer", def="hunter")

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Convert with dict()

: 쌍을 이룬 자료형의 나열을 dict화

You can also use the dict() function to convert two-value sequences into a dictionary.

You might run into such key-value sequences at times, such as “Strontium, 90, Carbon, 14.”

The first item in each sequence is used as the key and the second as the value.

First, here’s a small example using lol (a list of two-item lists):

>>> lol = [ ['a', 'b'], ['c', 'd'], ['e', 'f'] ]

>>> dict(lol)

{'a': 'b', 'c': 'd', 'e': 'f'}

We could have used any sequence containing two-item sequences. Here are other examples.

A list of two-item tuples:

>>> lot = [ ('a', 'b'), ('c', 'd'), ('e', 'f') ]

>>> dict(lot)

{'a': 'b', 'c': 'd', 'e': 'f'}

A tuple of two-item lists:

>>> tol = ( ['a', 'b'], ['c', 'd'], ['e', 'f'] )

>>> dict(tol)

{'a': 'b', 'c': 'd', 'e': 'f'}

A list of two-character strings:

>>> los = [ 'ab', 'cd', 'ef' ]

>>> dict(los)

{'a': 'b', 'c': 'd', 'e': 'f'}

A tuple of two-character strings:

>>> tos = ( 'ab', 'cd', 'ef' )

>>> dict(tos)

{'a': 'b', 'c': 'd', 'e': 'f'}

The section “Iterate Multiple Sequences with zip()” on page 110 introduces you to the zip() function, which makes it easy to create these two-item sequences.

Add or Change an Item by [ key ]

Adding an item to a dictionary is easy. Just refer to the item by its key and assign a value. If the key was already present in the dictionary, the existing value is replaced by the new one. If the key is new, it’s added to the dictionary with its value. Unlike lists, you don’t need to worry about Python throwing an exception during assignment by specifying an index that’s out of range.

Let’s make a dictionary of most of the members of Monty Python, using their last names as keys, and first names as values:

>>> pythons = {

... 'Chapman': 'Graham',

... 'Cleese': 'John',

... 'Idle': 'Eric',

... 'Jones': 'Terry',

... 'Palin': 'Michael',

... }

>>> pythons

{'Chapman': 'Graham', 'Cleese': 'John', 'Idle': 'Eric',

'Jones': 'Terry', 'Palin': 'Michael'}

We’re missing one member: the one born in America, Terry Gilliam. Here’s an attempt by an anonymous programmer to add him, but he’s botched the first name:

>>> pythons['Gilliam'] = 'Gerry'

>>> pythons

{'Chapman': 'Graham', 'Cleese': 'John', 'Idle': 'Eric',

'Jones': 'Terry', 'Palin': 'Michael', 'Gilliam': 'Gerry'}

And here’s some repair code by another programmer who is Pythonic in more than one way:

>>> pythons['Gilliam'] = 'Terry'

>>> pythons

{'Chapman': 'Graham', 'Cleese': 'John', 'Idle': 'Eric',

'Jones': 'Terry', 'Palin': 'Michael', 'Gilliam': 'Terry'}

By using the same key (‘Gilliam’), we replaced the original value ‘Gerry’ with ‘Terry’.

Remember that dictionary keys must be unique.

That’s why we used last names for keys instead of first names here — two members of Monty Python have the first name ‘Terry’! If you use a key more than once, the last value wins:

>>> some_pythons = {

... 'Graham': 'Chapman',

... 'John': 'Cleese',

... 'Eric': 'Idle',

... 'Terry': 'Gilliam',

... 'Michael': 'Palin',

... 'Terry': 'Jones',

... }

>>> some_pythons

{'Graham': 'Chapman', 'John': 'Cleese', 'Eric': 'Idle',

'Terry': 'Jones', 'Michael': 'Palin'}

We first assigned the value ‘Gilliam’ to the key ‘Terry’ and then replaced it with the value ‘Jones’.

Get an Item by [key] or with get()

- This is the most common use of a dictionary.

You specify the dictionary and *key*to get the corresponding value:

Using some_pythons from the previous section:

>>> some_pythons['John']

'Cleese'

If the key is not present in the dictionary, you’ll get an exception:

>>> some_pythons['Groucho']

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

keyError: 'Groucho'

- There are two good ways to avoid this. The first is to test for the key at the outset

by using in, as you saw in the previous section:

>>> 'Groucho' in some_pythons

False

- The second is to use the special dictionary

get() function. You provide the dictionary, key, and an optional value. If the key exists, you get its value:

>>> some_pythons.get('John')

'Cleese'

If not, you get the optional value, if you specified one:

>>> some_pythons.get('Groucho', 'Not a Python')

'Not a Python'

Otherwise, you get None (which displays nothing in the interactive interpreter):

>>> some_pythons.get('Groucho')

>>>

Get All keys with keys()

You can use keys() to get all of the keys in a dictionary. We’ll use a different sample dictionary for the next few examples:

>>> signals = {'green': 'go', 'yellow': 'go faster', 'red': 'smile for the camera'}

>>> signals.keys()

dict_keys(['green', 'yellow', 'red'])

In Python 2, keys() just returns a list. Python 3 returns dict_keys(), which is an iterable view of the keys. This is handy with large dictionaries because it doesn’t use the time and memory to create and store a list that you might not use. But often you actually do want a list. In Python 3, you need to call list() to convert a

dict_keysobject to a list.

>>> list( signals.keys() )

['green', 'yellow', 'red']

In Python 3, you also need to use the list() function to turn the results of values() and items() into normal Python lists. I use that in these examples.

Get All Values with values()

To obtain all the values in a dictionary, use values():

>>> list( signals.values() )

['go', 'go faster', 'smile for the camera']

Get All key-Value Pairs with items()

When you want to get all the key-value pairs from a dictionary, use the items() function:

>>> list( signals.items() )

[('green', 'go'), ('yellow', 'go faster'), ('red', 'smile for the camera')]

Each key and value is returned as a tuple, such as (‘green’, ‘go’).

Get Length with len()

Count your key-value pairs:

>>> len(signals)

3

Combine Dictionaries with {a, b}

Starting with Python 3.5, there’s a new way to merge dictionaries, using the ** unicorn glitter, which has a very different use in Chapter 9:

>>> first = {'a': 'agony', 'b': 'bliss'}

>>> second = {'b': 'bagels', 'c': 'candy'}

>>> {**first, **second}

{'a': 'agony', 'b': 'bagels', 'c': 'candy'}

Actually, you can pass more than two dictionaries:

>>> third = {'d': 'donuts'}

>>> {**first, **third, **second}

{'a': 'agony', 'b': 'bagels', 'd': 'donuts', 'c': 'candy'}

These are shallow copies.

See the discussion of deepcopy() (“Copy Everything with deepcopy()” on page 126 ) if you want full copies of the keys and values, with no connection to their origin dictionaries.

Combine Dictionaries with update()

You can use the update() function to copy the keys and values of one dictionary into another.

Let’s define the pythons dictionary, with all members:

>>> pythons = {

... 'Chapman': 'Graham',

... 'Cleese': 'John',

... 'Gilliam': 'Terry',

... 'Idle': 'Eric',

... 'Jones': 'Terry',

... 'Palin': 'Michael',

... }

>>> pythons

{'Chapman': 'Graham', 'Cleese': 'John', 'Gilliam': 'Terry',

'Idle': 'Eric', 'Jones': 'Terry', 'Palin': 'Michael'}

We also have a dictionary of other humorous persons called others:

>>> others = { 'Marx': 'Groucho', 'Howard': 'Moe' }

Now, along comes another anonymous programmer who decides that the members of others should be members of Monty Python:

>>> pythons.update(others)

>>> pythons

{'Chapman': 'Graham', 'Cleese': 'John', 'Gilliam': 'Terry',

'Idle': 'Eric', 'Jones': 'Terry', 'Palin': 'Michael',

'Marx': 'Groucho', 'Howard': 'Moe'}

병합되는 dictionary에 같은 key가 존재하면 값은 병합되는 값으로 변경된다 :

>>> first = {'a': 1, 'b': 2}

>>> second = {'b': 'platypus'}

>>> first.update(second)

>>> first

{'a': 1, 'b': 'platypus'}

Delete an Item by key with del

The previous pythons.update(others) code from our anonymous programmer was technically correct, but factually wrong. The members of others, although funny and famous, were not in Monty Python. Let’s undo those last two additions:

>>> del pythons['Marx']

>>> pythons

{'Chapman': 'Graham', 'Cleese': 'John', 'Gilliam': 'Terry',

'Idle': 'Eric', 'Jones': 'Terry', 'Palin': 'Michael',

'Howard': 'Moe'}

>>> del pythons['Howard']

>>> pythons

{'Chapman': 'Graham', 'Cleese': 'John', 'Gilliam': 'Terry',

'Idle': 'Eric', 'Jones': 'Terry', 'Palin': 'Michael'}

Get an Item by key and Delete It with pop()

This combines get() and del. If you give pop() a key and it exists in the dictionary, it returns the matching value and deletes the key-value pair. If it doesn’t exist, it raises an exception:

>>> len(pythons)

6

>>> pythons.pop('Palin')

'Michael'

>>> len(pythons)

5

>>> pythons.pop('Palin')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

keyError: 'Palin'

But if you give pop() a second default argument (as with get()), all is well and the dictionary is not changed:

>>> pythons.pop('First', 'Hugo')

'Hugo'

>>> len(pythons)

5

Delete All Items with clear()

To delete all keys and values from a dictionary, use clear() or just reassign an empty dictionary ({}) to the name:

>>> pythons.clear()

>>> pythons

{}

>>> pythons = {}

>>> pythons

{}

Test for a key with in

If you want to know whether a key exists in a dictionary, use in. Let’s redefine the pythons dictionary again, this time omitting a name or two:

>>> pythons = {'Chapman': 'Graham', 'Cleese': 'John',

... 'Jones': 'Terry', 'Palin': 'Michael', 'Idle': 'Eric'}

Now let’s see who’s in there:

>>> 'Chapman' in pythons

True

>>> 'Palin' in pythons

True

Did we remember to add Terry Gilliam this time?

>>> 'Gilliam' in pythons

False

Drat.

Assign with =

As with lists, if you make a change to a dictionary, it will be reflected in all the names that refer to it:

>>> signals = {'green': 'go',

... 'yellow': 'go faster',

... 'red': 'smile for the camera'}

>>> save_signals = signals

>>> signals['blue'] = 'confuse everyone'

>>> save_signals

{'green': 'go',

'yellow': 'go faster',

'red': 'smile for the camera',

'blue': 'confuse everyone'}

Copy with copy()

To actually copy keys and values from a dictionary to another dictionary and avoid this, you can use copy():

>>> signals = {'green': 'go',

... 'yellow': 'go faster',

... 'red': 'smile for the camera'}

>>> original_signals = signals.copy()

>>> signals['blue'] = 'confuse everyone'

>>> signals

{'green': 'go',

'yellow': 'go faster',

'red': 'smile for the camera',

'blue': 'confuse everyone'}

>>> original_signals

{'green': 'go',

'yellow': 'go faster',

'red': 'smile for the camera'}

>>>

This is a shallow copy, and works if the dictionary values are immutable (as they are in this case). If they aren’t, you need deepcopy().

Copy Everything with deepcopy()

Suppose that the value for red in the previous example was a list instead of a single string:

>>> signals = {'green': 'go',

... 'yellow': 'go faster',

... 'red': ['stop', 'smile']}

>>> signals_copy = signals.copy()

>>> signals

{'green': 'go',

'yellow': 'go faster',

'red': ['stop', 'smile']}

>>> signals_copy

{'green': 'go',

'yellow': 'go faster',

'red': ['stop', 'smile']}

>>>

Let’s change one of the values in the red list:

>>> signals['red'][1] = 'sweat'

>>> signals

{'green': 'go',

'yellow': 'go faster',

'red': ['stop', 'sweat']}

>>> signals_copy

{'green': 'go',

'yellow': 'go faster',

'red': ['stop', 'sweat']}

You get the usual change-by-either-name behavior. The copy() method copied the values as-is, meaning signal_copy got the same list value for ‘red’ that signals had.

The solution is deepcopy():

>>> import copy

>>> signals = {'green': 'go',

... 'yellow': 'go faster',

... 'red': ['stop', 'smile']}

>>> signals_copy = copy.deepcopy(signals)

>>> signals

{'green': 'go',

'yellow': 'go faster',

'red': ['stop', 'smile']}

>>> signals_copy

{'green': 'go',

'yellow':'go faster',

'red': ['stop', 'smile']}

>>> signals['red'][1] = 'sweat'

>>> signals

{'green': 'go',

'yellow': 'go faster',

red': ['stop', 'sweat']}

>>> signals_copy

{'green': 'go',

'yellow': 'go faster',

red': ['stop', 'smile']}

Compare Dictionaries

Much like lists and tuples in the previous chapter, dictionaries can be compared with the simple comparison operators == and != (그외 비교는 불가):

>>> a = {1:1, 2:2, 3:3}

>>> b = {3:3, 1:1, 2:2}

>>> a == b

True

Other operators won’t work:

>>> a = {1:1, 2:2, 3:3}

>>> b = {3:3, 1:1, 2:2}

>>> a <= b

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: '<=' not supported between instances of 'dict' and 'dict'

Python compares the keys and values one by one. The order in which they were originally created doesn’t matter. In this example, a and b are equal, except key 1 has the list value [1, 2] in a and the list value [1, 1] in b:

>>> a = {1: [1, 2], 2: [1], 3:[1]}

>>> b = {1: [1, 1], 2: [1], 3:[1]}

>>> a == b

False

Iterate with for and in

Iterating over a dictionary (or its keys() function) returns the keys.

In this example, the keys are the types of cards in the board game Clue (Cluedo outside of North America):

>>> accusation = {'room': 'ballroom', 'weapon': 'lead pipe',

... 'person': 'Col. Mustard'}

>>> for card in accusation: # or, for card in accusation.*keys()*:

... print (card)

room

weapon

person

To iterate over the values rather than the keys, you use the dictionary’s values() function:

>>> for value in accusation.values():

... print (value)

ballroom

lead pipe

Col. Mustard

To return both the key and value as a tuple, you can use the items() function:

>>> for item in accusation.items():

... print (item)

('room', 'ballroom')

('weapon', 'lead pipe')

('person', 'Col. Mustard')

You can assign to a tuple in one step. For each tuple returned by items(), assign the first value (the key) to card, and the second (the value) to contents:

>>> for card, contents in accusation.items():

... print ('Card', card, 'has the contents', contents)

Card weapon has the contents lead pipe

Card person has the contents Col. Mustard

Card room has the contents ballroom

dictionary Comprehensions

Not to be outdone by those bourgeois lists, dictionaries also have comprehensions.

The simplest form looks familiar:

{ key_expression : value_expression for expression in iterable }

>>> word = 'letters'

>>> letter_counts = {letter: word.count(letter) for letter in word}

>>> letter_counts

{'l': 1, 'e': 2, 't': 2, 'r': 1, 's': 1}

We’re running a loop over each of the seven letters in the string ‘letters’ and counting how many times that letter appears. Two uses of word.count(letter) are a waste of time because we have to count all the e’s twice and all the t’s twice. But when

we count the e’s the second time, we do no harm because we just replace the entry in the dictionary that was already there; the same goes for counting the t’s. So, the following would have been a teeny bit more Pythonic:

>>> word = 'letters'

>>> letter_counts = {letter: word.count(letter) for letter in set(word)}

>>> letter_counts

{'t': 2, 'l': 1, 'e': 2, 'r': 1, 's': 1}

The dictionary’s keys are in a different order than the previous example because iterating set(word) returns letters in a different order than iterating the string word.

Similar to list comprehensions, dictionary comprehensions can also have if tests and multiple for clauses:

{ key_expression : value_expression for expression in iterable if condition }

>>> vowels = 'aeiou'

>>> word = 'onomatopoeia'

>>> vowel_counts = {letter: word.count(letter) for letter in set(word)

if letter in vowels}

>>> vowel_counts

{'e': 1, 'i': 1, 'o': 4, 'a': 2}

See PEP-274 for more examples of dictionary comprehensions.

Sets

A set is like a dictionary with its values thrown away, leaving only the keys. As with a dictionary, each key must be unique. You use a set when you only want to know that something exists, and nothing else about it. It’s a bag of keys. Use a dictionary if you want to attach some information to the key as a value.

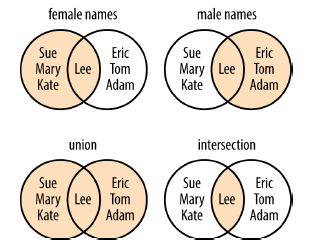

At some bygone time, in some places, set theory was taught in elementary school along with basic mathematics. If your school skipped it (or you were staring out the window), Figure 8-1 shows the ideas of set union and intersection.

Suppose that you take the union of two sets that have some keys in common. Because a set must contain only one of each item, the union of two sets will contain only one of each key. The null or empty set is a set with zero elements. In Figure 8-1, an example of a null set would be female names beginning with X.

Create with set()

To create a set, you use the set() function or enclose one or more comma-separated values in curly brackets, as shown here:

>>> empty_set = set()

>>> empty_set

set()

>>> even_numbers = {0, 2, 4, 6, 8}

>>> even_numbers

{0, 2, 4, 6, 8}

>>> odd_numbers = {1, 3, 5, 7, 9}

>>> odd_numbers

{1, 3, 5, 7, 9}

Sets are unordered.

Because [] creates an empty list, you might expect {} to create an empty set. Instead, {} creates an empty dictionary. That’s also why the interpreter prints an empty set as set() instead of {}. Why?

Dictionaries were in Python first and took possession of the curly brackets. And possession is nine-tenths of the law.^2

Convert with set()

You can create a set from a list, string, tuple, or dictionary, discarding any duplicate values.

First, let’s take a look at a string with more than one occurrence of some letters:

>>> set( 'letters' )

{'l', 'r', 's', 't', 'e'}

Notice that the set contains only one ‘e’ or ‘t’, even though ‘letters’ contained two of each.

Now, let’s make a set from a list:

>>> set( ['Dasher', 'Dancer', 'Prancer', 'Mason-Dixon'] )

{'Dancer', 'Dasher', 'Mason-Dixon', 'Prancer'}

This time, a set from a tuple:

>>> set( ('Ummagumma', 'Echoes', 'Atom Heart Mother') )

{'Ummagumma', 'Atom Heart Mother', 'Echoes'}

When you give set() a dictionary, it uses only the keys:

>>> set( {'apple': 'red', 'orange': 'orange', 'cherry': 'red'} )

{'cherry', 'orange', 'apple'}

Get Length with len()

Let’s count our reindeer:

>>> reindeer = set( ['Dasher', 'Dancer', 'Prancer', 'Mason-Dixon'] )

>>> len(reindeer)

4

Add an Item with add()

Throw another item into a set with the set add() method:

>>> s = set((1,2,3))

>>> s

{1, 2, 3}

>>> s.add(4)

>>> s

{1, 2, 3, 4}

Delete an Item with remove()

You can delete a value from a set by value:

>>> s = set((1,2,3))

>>> s.remove(3)

>>> s

{1, 2}

Iterate with for and in

Like dictionaries, you can iterate over all items in a set:

>>> furniture = set(('sofa', 'ottoman', 'table'))

>>> for piece in furniture:

... print (piece)

ottoman

table

sofa

Test for a Value with in

This is the most common use of a set. We’ll make a dictionary called drinks. Each key is the name of a mixed drink, and the corresponding value is a set of that drink’s ingredients:

>>> drinks = {

... 'martini': {'vodka', 'vermouth'},

... 'black russian': {'vodka', 'kahlua'},

... 'white russian': {'cream', 'kahlua', 'vodka'},

... 'manhattan': {'rye', 'vermouth', 'bitters'},

... 'screwdriver': {'orange juice', 'vodka'}

... }

Even though both are enclosed by curly braces ({ and }), a set is just a bunch of values, and a dictionary contains key : value pairs.

Which drinks contain vodka?

>>> for name, contents in drinks.items():

... if 'vodka' in contents:

... print (name)

...

screwdriver

martini

black russian

white russian

We want something with vodka but are lactose intolerant, and think vermouth tastes like kerosene:

>>> for name, contents in drinks.items():

... if 'vodka' in contents and not ('vermouth' in contents or

... 'cream' in contents):

... print (name)

...

screwdriver

black russian

We’ll rewrite this a bit more succinctly in the next section.

Combinations and Operators

What if you want to check for combinations of set values? Suppose that you want to find any drink that has orange juice or vermouth? Let’s use the set intersection operator, which is an ampersand (&):

>>> for name, contents in drinks.items():

... if contents & {'vermouth', 'orange juice'}:

... print (name)

...

screwdriver

martini

manhattan

The result of the & operator is a set that contains all of the items that appear in both lists that you compare. If neither of those ingredients were in contents, the & returnsan empty set, which is considered False. Now, let’s rewrite the example from the previous section, in which we wanted vodka but neither cream nor vermouth:

>>> for name, contents in drinks.items():

... if 'vodka' in contents and not contents & {'vermouth', 'cream'}:

... print (name)

...

screwdriver

black russian

Figure 8-1. Common things to do with sets

Let’s save the ingredient sets for these two drinks in variables, just to save our delicate fingers some typing in the coming examples:

>>> bruss = drinks['black russian']

>>> wruss = drinks['white russian']

>>> a = {1, 2}

>>> b = {2, 3}

# 교집합

# a.intersection(b)

# a & b

>>> a & b

>>> a.intersection(b)

{2}

# 합집합

# a.union(b)

# a | b

>>> a | b

>>> a.union(b)

{1, 2, 3}

# 차집합

# a.difference(b)

# a - b

>>> a - b

>>> a.difference(b)

{1}

# exclusive

# a.symmetric_difference(b)

# a ^ b

>>> a ^ b

>>> a.symmetric_difference(b)

{1, 3}

# 부분집합 - 하위집합

# a.issubset(b)

# a <= b

>>> a <= b

False

>>> a.issubset(b)

False

>>> a <= a

True

>>> a.issubset(a)

True

# 진부분집합 - 하위집합

# a < b

>>> a < b

False

>>> a < a

False

# 부분집합 - 상위집합

# a.issuperset(b)

# a >= b

>>> a >= b

False

>>> a.issuperset(b)

False

>>> wruss >= bruss

True

>>> a >= a

True

>>> a.issuperset(a)

True

# 부분집합 - 진상위집합

# a > b

>>> a > b

False

>>> wruss > bruss

True

>>> a > a

False

Set Comprehensions

{ expression for expression in iterable }

{ expression for expression in iterable if condition }

>>> a_set = {number for number in range(1,6) if number % 3 == 1}

>>> a_set

{1, 4}

Create an Immutable Set with frozenset()

If you want to create a set that can’t be changed, call the frozenset() function with any iterable argument:

>>> frozenset([3, 2, 1])

frozenset({1, 2, 3})

>>> frozenset(set([2, 1, 3]))

frozenset({1, 2, 3})

>>> frozenset({3, 1, 2})

frozenset({1, 2, 3})

>>> frozenset( (2, 3, 1) )

frozenset({1, 2, 3})

Is it really frozen?

>>> fs = frozenset([3, 2, 1])

>>> fs

frozenset({1, 2, 3}) # 자료형이 frozenset이다.

>>> fs.add(4)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'frozenset' object has no attribute 'add'

Yes, pretty frosty.

Data Structures So Far

To review, you make:

- A list by using square brackets ([])

- A tuple by using commas and optional parentheses

- A dictionary or set by using curly brackets ({})

For all but sets, you access a single element with square brackets. For the list and tuple, the value between the square brackets is an integer offset. For the dictionary, it’s a key. For all three, the result is a value. For the set, it’s either there or it’s not; there’s no index or key:

>>> marx_list = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> marx_tuple = ('Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo')

>>> marx_dict = {'Groucho': 'banjo', 'Chico': 'piano', 'Harpo': 'harp'}

>>> marx_set = {'Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo'}

>>> marx_list[2]

'Harpo'

>>> marx_tuple[2]

'Harpo'

>>> marx_dict['Harpo']

'harp'

>>> 'Harpo' in marx_list

True

>>> 'Harpo' in marx_tuple

True

>>> 'Harpo' in marx_dict

True

>>> 'Harpo' in marx_set

True

Make Bigger Data Structures

We worked up from simple booleans, numbers, and strings to lists, tuples, sets, and dictionaries. You can combine these built-in data structures into bigger, more complex structures of your own. Let’s start with three different lists:

>>> marxes = ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo']

>>> pythons = ['Chapman', 'Cleese', 'Gilliam', 'Jones', 'Palin']

>>> stooges = ['Moe', 'Curly', 'Larry']

We can make a tuple that contains each list as an element:

>>> tuple_of_lists = marxes, pythons, stooges

>>> tuple_of_lists

(['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo'],

['Chapman', 'Cleese', 'Gilliam', 'Jones', 'Palin'],

['Moe', 'Curly', 'Larry'])

And we can make a list that contains the three lists:

>>> list_of_lists = [marxes, pythons, stooges]

>>> list_of_lists

[['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo'],

['Chapman', 'Cleese', 'Gilliam', 'Jones', 'Palin'],

['Moe', 'Curly', 'Larry']]

Finally, let’s create a dictionary of lists. In this example, let’s use the name of the comedy group as the key and the list of members as the value:

>>> dict_of_lists = {'Marxes': marxes, 'Pythons': pythons, 'Stooges': stooges}

>> dict_of_lists

{'Marxes': ['Groucho', 'Chico', 'Harpo'],

'Pythons': ['Chapman', 'Cleese', 'Gilliam', 'Jones', 'Palin'],

'Stooges': ['Moe', 'Curly', 'Larry']}

Your only limitations are those in the data types themselves. For example, dictionary keys need to be immutable, so a list, dictionary, or set can’t be a key for another dictionary. But a tuple can be. For example, you could index sites of interest by GPS coordinates (latitude, longitude, and altitude; see Chapter 21 for more mapping examples):

>>> houses = {

(44.79, -93.14, 285): 'My House',

(38.89, -77.03, 13): 'The White House'

}

Coming Up

Back to code structures. You’ll learn how to wrap code in functions, and how to deal with exceptions when things go awry.

Things to Do

8.1 Make an English-to-French dictionary called e2f and print it. Here are your starter words: dog is chien, cat is chat, and walrus is morse.

8.2 Using your three-word dictionary e2f, print the French word for walrus.

8.3 Make a French-to-English dictionary called f2e from e2f. Use the items method.

8.4 Print the English equivalent of the French word chien.

8.5 Print the set of English words from e2f.

english = ['dog','cat','walrus']

french =['chien','chat','morse']

e2f = dict(zip(english,french))

print(e2f)

print(e2f['walrus'])

# 프랑스-영어 사전

f2e = {v:k for k,v in e2f.items()}

print(f2e)

# values 출력

print(list(f2e.values()))

8.6 Make a multilevel dictionary called life. Use these strings for the topmost keys: ‘animals’, ‘plants’, and ‘other’. Make the ‘animals’ key refer to another dictionary with the keys ‘cats’, ‘octopi’, and ‘emus’. Make the ‘cats’ key refer to a list of strings with the values ‘Henri’, ‘Grumpy’, and ‘Lucy’. Make all the other keys refer to empty dictionaries.

8.7 Print the top-level keys of life.

8.8 Print the keys for life[‘animals’].

8.9 Print the values for life[‘animals’][‘cats’].

life = {

'animals':{

'cats':['Henri', 'Grumpy', 'Lucy'],

'octopi':{},

'emus':{}

},

'plants':{},

'other':{}

}

for i in life: # life.keys() 도 가능

print(i)

for i in life['animals']: # life['animals'].keys() 도 가능

print(i)

for i in life['animals']['cats']: # life['animals']['cats'].keys() 도 가능

print(i)

8.10 Use a dictionary comprehension to create the dictionary squares. Use range(10) to return the keys, and use the square of each key as its value. 8.11 Use a set comprehension to create the set odd from the odd numbers in range(10). 8.12 Use a generator comprehension to return the string ‘Got ‘ and a number for the numbers in range(10). Iterate through this by using a for loop. 8.13 Use zip() to make a dictionary from the key tuple (‘optimist’, ‘pessimist’, ‘troll’) and the values tuple (‘The glass is half full’, ‘The glass is half empty’, ‘How did you get a glass?’). 8.14 Use zip() to make a dictionary called movies that pairs these lists: titles = [‘Creature of Habit’, ‘Crewel Fate’, ‘Sharks On a Plane’] and plots = [‘A nun turns into a monster’, ‘A haunted yarn shop’, ‘Check your exits’]

squares = { i: i**2 for i in range(10)}

print(squares)

new_set = { i for i in range(10) if i%2 != 0}

print(new_set)

for thing in ('Got %s' % number for number in range(10)):

print (thing)

keys = ('optimist', 'pessimist', 'troll')

values = ('The glass is half full', 'The glass is half empty', 'How did you get a glass?')

result = dict(zip(keys, values))

print(result)

titles = ['Creature of Habit','Crewel Fate','Sharks On a Plane']

plots = ['A nun turns into a monster','A haunted yarn shop','Check your exits']

movies = dict(zip(titles, plots))

print(movies)

딕셔너리 응용

딕셔너리에 키-값 쌍 추가하기

딕셔너리의 중요한 기능 중 하나가 바로 키-값 쌍 추가입니다.

- setdefault: 키-값 쌍 추가

- update: 키의 값 수정, 키가 없으면 키-값 쌍 추가

딕셔너리에 키와 기본값 저장하기

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

x.setdefault('e') # x['e'] = None

print(x) # {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40, 'e': None}

x.setdefault('f', 100) #x['f'] = 100

print(x) # {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40, 'e': None, 'f': 100}

딕셔너리에서 키의 값 수정하기

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

x.update(a=90)

print(x) # {'a': 90, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

x.update(a=900, f=60)

print(x) # {'a': 900, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40, 'f': 60}

y = {1: 'one', 2: 'two'}

y.update({1: 'ONE', 3: 'THREE'})

print(y) # {1: 'ONE', 2: 'two', 3: 'THREE'}

y.update([[2, 'TWO'], [4, 'FOUR']])

print(y) # {1: 'ONE', 2: 'TWO', 3: 'THREE', 4: 'FOUR'}

y.update(zip([1, 2], ['one', 'two']))

print(y) # {1: 'one', 2: 'two', 3: 'THREE', 4: 'FOUR'}

[참고] setdefault와 update의 차이 setdefault는 키-값 쌍 추가만 할 수 있고, 이미 들어있는 키의 값은 수정할 수 없습니다.

하지만 update는 키-값 쌍 추가와 값 수정이 모두 가능합니다.

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

x.setdefault('a', 90)

print(x) # {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

딕셔너리에서 키-값 쌍 삭제하기

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

x.pop('a')

print(x) # {'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

result = x.pop('z', 0) # 삭제할 key가 없을 때 반환할 값 지정

print(result) # 0

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

del x['a'] # 10

print(x) # {'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

딕셔너리에서 임의의 키-값 쌍 삭제하기

popitem()은 딕셔너리에서 마지막 키-값 쌍을 삭제한 뒤 삭제한 키-값 쌍을 튜플로 반환합니다.

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

result = x.popitem()

print(result) # ('d', 40)

print(x) # {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30}

딕셔너리의 모든 키-값 쌍을 삭제하기

clear()는 딕셔너리의 모든 키-값 쌍을 삭제합니다. 다음은 딕셔너리 x의 모든 키-값 쌍을 삭제하여 빈 딕셔너리 {}가 됩니다.

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

x.clear()

print(x) # {}

딕셔너리에서 키의 값을 가져오기

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

result = x.get('a')

print(result) # 10

result = x.get('z', 0) # key가 없을 때 반환할 값 지정

print(result) # 0

딕셔너리에서 모든 데이터 가져오기 : 키-값 쌍, 키, 값

- items: 키-값 쌍을 모두 가져옴

- keys: 키를 모두 가져옴

- values: 값을 모두 가져옴

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

result = x.items()

print(result) # dict_items([('a', 10), ('b', 20), ('c', 30), ('d', 40)])

result = x.keys()

print(result) # dict_keys(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'])

result = x.values()

print(result) # dict_values([10, 20, 30, 40])

리스트와 튜플로 딕셔너리 만들기

dict.fromkeys(키리스트)는 키 리스트로 딕셔너리를 생성하며 값은 모두 None으로 저장합니다. dict.fromkeys(키리스트, 값)처럼 키 리스트와 값을 지정하면 해당 값이 키의 값으로 저장됩니다.

keys = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

x = dict.fromkeys(keys)

print(x) # {'a': None, 'b': None, 'c': None, 'd': None}

y = dict.fromkeys(keys, 100)

print(y) # {'a': 100, 'b': 100, 'c': 100, 'd': 100}

defaultdict 사용하기

지금까지 사용한 딕셔너리(dict)는 없는 키에 접근했을 경우 에러가 발생합니다. defaultdict는 없는 키에 접근하더라도 에러가 발생하지 않으며 기본값을 반환합니다. defaultdict는 collections 모듈에 들어있으며 기본값 생성 함수를 넣습니다.

defaultdict(기본값생성함수)

x = {'a': 0, 'b': 0, 'c': 0, 'd': 0}

x['z'] # 키 'z'는 없음

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#5>", line 1, in <module>

x['z']

KeyError: 'z'

from collections import defaultdict # collections 모듈에서 defaultdict를 가져옴

y = defaultdict(int) # int로 기본값 생성

y['z']

print(y) # defaultdict(<class 'int'>, {'z': 0})

z = defaultdict(lambda: 'python')

z['a']

z[0]

print(z) # defaultdict(<function <lambda> at 0x00000281C533D120>, {'a': 'python', 0: 'python'})

딕셔너리 표현식 사용하기

- {키: 값 for 키, 값 in 딕셔너리}

- dict({키: 값 for 키, 값 in 딕셔너리})

keys = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

# {'a': None, 'b': None, 'c': None, 'd': None}

d1 = dict.fromkeys(keys)

d = { k:v for k,v in dict.fromkeys(keys).items()}

# {'a': 0, 'b': 0, 'c': 0, 'd': 0}

d1 = dict.fromkeys(keys,0)

d = { k:0 for k,v in dict.fromkeys(keys).items()}

d3 = { k:0 for k in dict.fromkeys(keys).keys()}

d2 = { k:0 for k in keys}

딕셔너리 표현식에서 if 조건문 사용하기

- for문에서 dictionary의 변경이 발생하면 에러 발생

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

for key, value in x.items():

if value == 20: # 값이 20이면

del x[key] # 키-값 쌍 삭제

print(x)

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

x = {key: value for key, value in x.items() if value != 20} #값이 20인 항목 제외

print(x) # {'a': 10, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

x = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

x = {key: value for key, value in x.items() if key != 'a'} #key가 'a'인 항목 제외

print(x) # {'b': 20, 'c': 30, 'd': 40}

딕셔너리 안에서 딕셔너리 사용하기

- 딕셔너리 = {키1: {키A: 값A}, 키2: {키B: 값B}}

- 딕셔너리[key1][key2] 형식으로 접근

- 딕셔너리[key1][key2] = 값 형식으로 값 할당

from collections import defaultdict

student = ['정길주','박승화','임태익']

sub = ['kor','math','eng']

kor = [100,25,88]

math = [78,99,75]

eng = [77,88,77]

dic = defaultdict(int)

t = list(zip(student,kor,math,eng))

for i in t:

sub_dict = {}

for j in range(3):

sub_dict['kor'] = i[1]

sub_dict['math'] = i[2]

sub_dict['eng'] = i[3]

dic.setdefault(i[0],sub_dict)

print(dict(dic))

set 정리

| 메서드 | 집합 연산자 | 설명 |

|---|---|---|

| set.union(세트1, 세트2) | | | 두 세트의 합집합 |

| set.intersection(세트1, 세트2) | & | 두 세트의 교집합 |

| set.difference(세트1, 세트2) | - | 두 세트의 차집합 |

| set.symmetric_difference(세트1, 세트2) | ^ | 두 세트의 대칭차집합 |

| update(다른세트) | |= | 현재 세트에 다른 세트를 더함 |

| intersection_update(다른세트) | &= | 현재 세트와 다른 세트 중에서 겹치는 요소만 현재 세트에 저장 |

| difference_update(다른세트) | -= | 현재 세트에서 다른 세트를 뺌 |

| symmetric_difference_update(다른세트) | ^= | 현재 세트와 다른 세트 중에서 겹치지 않는 요소만 현재 세트에 저장 |

| issubset(다른세트) | <= | 현재 세트가 다른 세트의 부분집합인지 확인 |

| < | 현재 세트가 다른 세트의 진부분집합인지 확인 | |

| issuperset(다른세트) | >= | 현재 세트가 다른 세트의 상위집합인지 확인 |

| > | 현재 세트가 다른 세트의 진상위집합인지 확인 | |

| isdisjoint(다른세트) | 현재 세트가 다른 세트와 겹치지 않는지 확인 | |

| add(요소) | 세트에 요소를 추가 | |

| remove(요소) | 세트에서 특정 요소를 삭제, 없으면 에러 발생 | |

| discard(요소) | 세트에서 특정 요소를 삭제, 요소가 없으면 그냥 넘어감 | |

| pop() | 세트에서 임의의 요소를 삭제하고 해당 요소를 반환 | |

| clear() | 세트에서 모든 요소를 삭제 | |

| copy() | 세트를 복사하여 새로운 세트 생성 |

Set 표현식

{식 for 변수 in 반복가능한값}

set(식 for 변수 in 반복가능한값)

{i for i in ‘apple’}

{식 for 변수 in 세트 if 조건식}

set(식 for 변수 in 세트 if 조건식)

{i for i in ‘pineapple’ if i not in ‘apl’}